Coastal waters were an oxygen oasis 2.3 billion years ago

Earth was momentarily ripe for the evolution of animals hundreds of millions of years before they first appeared, researchers propose.

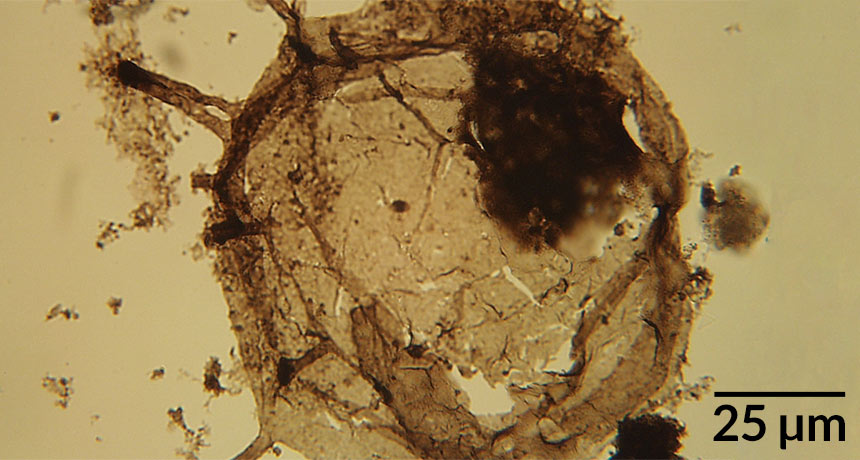

Chemical clues in ancient rocks suggest that 2.32 billion to 2.1 billion years ago, shallow coastal waters held enough oxygen to support oxygen-hungry life-forms including some animals, researchers report the week of January 16 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. But the first animal fossils, sponges, don’t appear until around 650 million years ago, following a period of scant oxygen known as the boring billion (SN: 11/14/15, p. 18).

“As far as environmental conditions were concerned, things were favorable for this evolutionary step to happen,” says study coauthor Andrey Bekker, a sedimentary geologist at the University of California, Riverside. Something else must have stalled the rise of animals, he says.

Microbes began flooding Earth with oxygen around 2.3 billion years ago during the Great Oxidation Event. This breath of oxygen enabled the eventual emergence of complex, oxygen-dependent life-forms called eukaryotes, an evolutionary line that would later include animals and plants. Scientists have proposed that the Great Oxidation Event wasn’t a smooth rise, but contained an “overshoot” during which oxygen concentrations momentarily peaked before dropping to a lower, stable level during the boring billion. Whether that overshoot was enough to support animals was unclear, though.

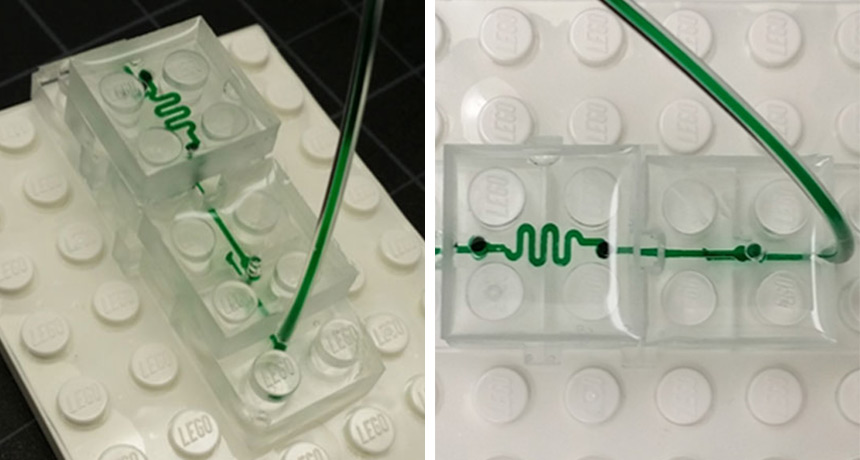

Bekker and colleagues tackled this question using a relatively new way to measure ancient oxygen. Rock weathering can wash the element selenium into the oceans. In oxygen-free waters, all of the selenium settles onto the seafloor. But in water with at least some oxygen, only a fraction of the selenium is deposited. And the selenium that is laid down is disproportionately that of a lighter isotope of the element, leaving atoms of a heavier isotope to be deposited elsewhere.

If ancient coasts contained relatively abundant oxygen, the researchers expected to find more light selenium close to shore and more heavy selenium in deeper, oxygen-deprived waters. Analyzing shales formed under deep waters around the world, the researchers found just such an isotope segregation. These shales had an abundance of the heavier selenium, leading researchers to infer that the lighter version of the element was concentrated closer to shore.

Oxygen concentrations in coastal waters were at least nearly one percent of present-day levels and “were flirting with the limits of what complex life can survive,” proposes study coauthor Michael Kipp, a geochemist at the University of Washington in Seattle. While the environment was probably suitable for eukaryotes, life hadn’t evolved enough by this point to take advantage of the situation, Kipp proposes. The appearance of eukaryotes in the fossil record would take hundreds of millions of years of more evolution (SN Online: 5/18/16), he says, and the first animals even longer.

Tracking selenium is such a new technique, though, that “interpretations could change as we better understand how it works,” says Philip Pogge von Strandmann, a geochemist at University College London. Currently the method is “tricky,” he says, especially for precisely estimating oxygen concentrations.