CRISPR adds storing movies to its feats of molecular biology

Short film is alive and well. Using the current trendy gene-editing system CRISPR, a team from Harvard University has encoded images and a short movie into the DNA of living bacteria.

The work is part of a larger effort to use DNA to store data — from audio recordings and poetry to entire books on synthetic biology. Last year, Seth Shipman and his colleagues at Harvard threw CRISPR into the mix when they used the editing system to record molecular data in the DNA of Escherichia coli.

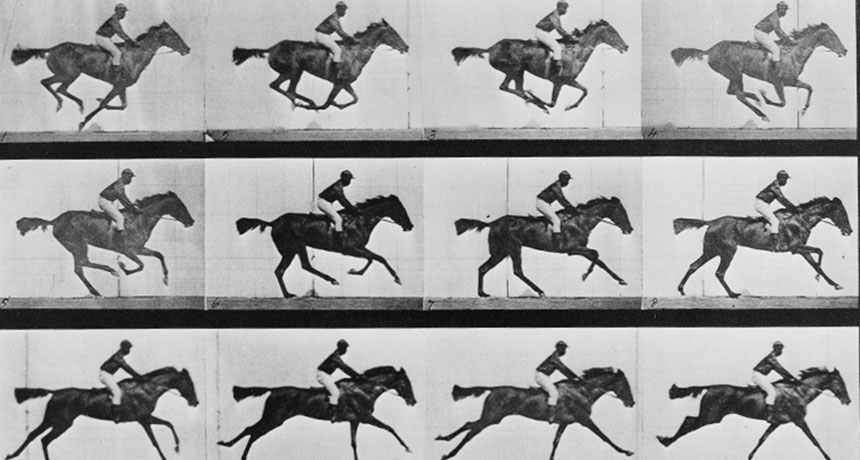

Now, the team is upping its game with images of a human hand and a short movie, a GIF of a galloping horse from iconic turn-of-the-century photographer Eadweard Muybridge’s Human and Animal Locomotion. In the code, the nucleotide bases that form DNA correspond to black-and-white pixel values. The video was encoded frame by frame. Once the team synthesized the DNA, they used CRISPR and two associated Cas proteins (Cas 1 and 2) to slip the data into the genetic blueprint of E. coli colonies.

After growing the bacteria for several generations, the scientists retrieved the code for the images and film frames and were able to reconstruct the clips. About 90 percent of the encoded information was left intact. Though it’s not a perfect storage system, the results demonstrate CRISPR’s potential for hiding data in the genetic blueprints of bacteria, Shipman and his colleagues write July 12 in Nature.