Consider everything your smartphone has done for you today. Counted your steps? Deposited a check? Transcribed notes? Navigated you somewhere new?

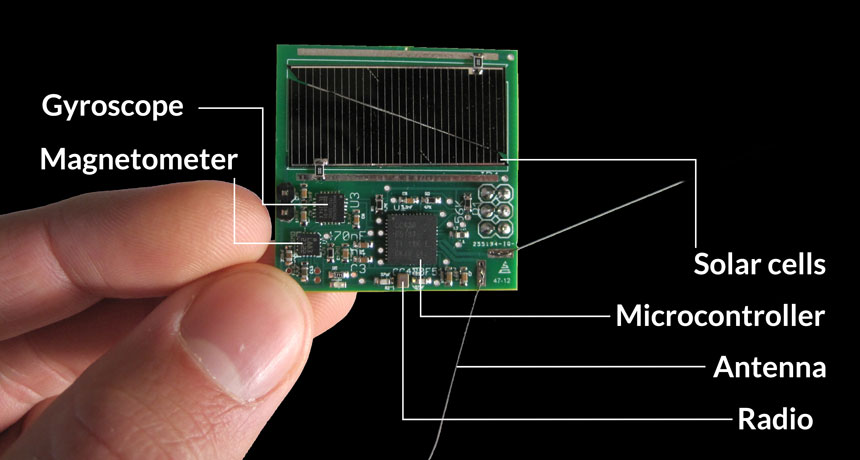

Smartphones make for such versatile pocket assistants because they’re equipped with a suite of sensors, including some we may never think — or even know — about, sensing, for example, light, humidity, pressure and temperature.

Because smartphones have become essential companions, those sensors probably stayed close by throughout your day: the car cup holder, your desk, the dinner table and nightstand. If you’re like the vast majority of American smartphone users, the phone’s screen may have been black, but the device was probably on the whole time.

“Sensors are finding their ways into every corner of our lives,” says Maryam Mehrnezhad, a computer scientist at Newcastle University in England. That’s a good thing when phones are using their observational dexterity to do our bidding. But the plethora of highly personal information that smartphones are privy to also makes them powerful potential spies.

Online app store Google Play has already discovered apps abusing sensor access. Google recently booted 20 apps from Android phones and its app store because the apps could — without the user’s knowledge — record with the microphone, monitor a phone’s location, take photos, and then extract the data. Stolen photos and sound bites pose obvious privacy invasions. But even seemingly innocuous sensor data can potentially broadcast sensitive information. A smartphone’s movement may reveal what users are typing or disclose their whereabouts. Even barometer readings that subtly shift with increased altitude could give away which floor of a building you’re standing on, suggests Ahmed Al-Haiqi, a security researcher at the National Energy University in Kajang, Malaysia.

These sneaky intrusions may not be happening in real life yet, but concerned researchers in academia and industry are working to head off eventual invasions. Some scientists have designed invasive apps and tested them on volunteers to shine a light on what smartphones can reveal about their owners. Other researchers are building new smartphone security systems to help protect users from myriad real and hypothetical privacy invasions, from stolen PIN codes to stalking.

Message revealed

Motion detectors within smartphones, like the accelerometer and the rotation-sensing gyroscope, could be prime tools for surreptitious data collection. They’re not permission protected — the phone’s user doesn’t have to give a newly installed app permission to access those sensors. So motion detectors are fair game for any app downloaded onto a device, and “lots of vastly different aspects of the environment are imprinted on those signals,” says Mani Srivastava, an engineer at UCLA.

For instance, touching different regions of a screen makes the phone tilt and shift just a tiny bit, but in ways that the phone’s motion sensors pick up, Mehrnezhad and colleagues demonstrated in a study reported online April 2017 in the International Journal of Information Security. These sensors’ data may “look like nonsense” to the human eye, says Al-Haiqi, but sophisticated computer programs can discern patterns in the mess and match segments of motion data to taps on various areas of the screen.

For the most part, these computer programs are machine-learning algorithms, Al-Haiqi says. Researchers train them to recognize keystrokes by feeding the programs a bunch of motion sensor data labeled with the key tap that produces particular movement. A pair of researchers built TouchLogger, an app that collects orientation sensor data and uses the data to deduce taps on smartphones’ number keyboards. In a test on HTC phones, reported in 2011 in San Francisco at the USENIX Workshop on Hot Topics in Security, TouchLogger discerned more than 70 percent of key taps correctly.

Since then, a spate of similar studies have come out, with scientists writing code to infer keystrokes on number and letter keyboards on different kinds of phones. In 2016 in Pervasive and Mobile Computing, Al-Haiqi and colleagues reviewed these studies and concluded that only a snoop’s imagination limits the ways motion data could be translated into key taps. Those keystrokes could divulge everything from the password entered on a banking app to the contents of an e-mail or text message.

Story continues below graphs

A more recent application used a whole fleet of smartphone sensors — including the gyroscope, accelerometer, light sensor and magnetism-measuring magnetometer — to guess PINs. The app analyzed a phone’s movement and how, during typing, the user’s finger blocked the light sensor. When tested on a pool of 50 PIN numbers, the app could discern keystrokes with 99.5 percent accuracy, the researchers reported on the Cryptology ePrint Archive in December.

Other researchers have paired motion data with mic recordings, which can pick up the soft sound of a fingertip tapping a screen. One group designed a malicious app that could masquerade as a simple note-taking tool. When the user tapped on the app’s keyboard, the app covertly recorded both the key input and the simultaneous microphone and gyroscope readings to learn the sound and feel of each keystroke.

The app could even listen in the background when the user entered sensitive info on other apps. When tested on Samsung and HTC phones, the app, presented in the Proceedings of the 2014 ACM Conference on Security and Privacy in Wireless and Mobile Networks, inferred the keystrokes of 100 four-digit PINs with 94 percent accuracy.

Al-Haiqi points out, however, that success rates are mostly from tests of keystroke-deciphering techniques in controlled settings — assuming that users hold their phones a certain way or sit down while typing. How these info-extracting programs fare in a wider range of circumstances remains to be seen. But the answer to whether motion and other sensors would open the door for new privacy invasions is “an obvious yes,” he says.

Tagalong

Motion sensors can also help map a person’s travels, like a subway or bus ride. A trip produces an undercurrent of motion data that’s discernible from shorter-lived, jerkier movements like a phone being pulled from a pocket. Researchers designed an app, described in 2017 in IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security, to extract the data signatures of various subway routes from accelerometer readings.

In experiments with Samsung smartphones on the subway in Nanjing, China, this tracking app picked out which segments of the subway system a user was riding with at least 59, 81 and 88 percent accuracy — improving as the stretches expanded from three to five to seven stations long. Someone who can trace a user’s subway movements might figure out where the traveler lives and works, what shops or bars the person frequents, a daily schedule, or even — if the app is tracking multiple people — who the user meets at various places.

Accelerometer data can also plot driving routes, as described at the 2012 IEEE International Conference on Communication Systems and Networks in Bangalore, India. Other sensors can be used to track people in more confined spaces: One team synced a smartphone mic and portable speaker to create an on-the-fly sonar system to map movements throughout a house. The team reported the work in the September 2017 Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies.

“Fortunately there is not anything like [these sensor spying techniques] in real life that we’ve seen yet,” says Selcuk Uluagac, an electrical and computer engineer at Florida International University in Miami. “But this doesn’t mean there isn’t a clear danger out there that we should be protecting ourselves against.”

That’s because the kinds of algorithms that researchers have employed to comb sensor data are getting more advanced and user-friendly all the time, Mehrnezhad says. It’s not just people with Ph.D.s who can design the kinds of privacy invasions that researchers are trying to raise awareness about. Even app developers who don’t understand the inner workings of machine-learning algorithms can easily get this kind of code online to build sensor-sniffing programs.

What’s more, smartphone sensors don’t just provide snooping opportunities for individual cybercrooks who peddle info-stealing software. Legitimate apps often harvest info, such as search engine and app download history, to sell to advertising companies and other third parties. Those third parties could use the information to learn about aspects of a user’s life that the person doesn’t necessarily want to share.

Take a health insurance company. “You may not like them to know if you are a lazy person or you are an active person,” Mehrnezhad says. “Through these motion sensors, which are reporting the amount of activity you’re doing every day, they could easily identify what type of user you are.”

Sensor safeguards

Since it’s only getting easier for an untrusted third party to make private inferences from sensor data, researchers are devising ways to give people more control over what information apps can siphon off of their devices. Some safeguards could appear as standalone apps, whereas others are tools that could be built into future operating system updates.

Uluagac and colleagues proposed a system called 6thSense, which monitors a phone’s sensor activity and alerts its owner to unusual behavior, in Vancouver at the August 2017 USENIX Security Symposium. The user trains this system to recognize the phone’s normal sensor behavior during everyday tasks like calling, Web browsing and driving. Then, 6thSense continually checks the phone’s sensor activity against these learned behaviors.

If someday the program spots something unusual — like the motion sensors reaping data when a user is just sitting and texting — 6thSense alerts the user. Then the user can check if a recently downloaded app is responsible for this suspicious activity and delete the app from the phone.

Uluagac’s team recently tested a prototype of the system: Fifty users trained Samsung smartphones with 6thSense to recognize their typical sensor activity. When the researchers fed the 6thSense system examples of benign data from daily activities mixed in with segments of malicious sensor operations, 6thSense picked out the problematic bits with over 96 percent accuracy.

For people who want more active control over their data, Supriyo Chakraborty, a privacy and security researcher at IBM in Yorktown Heights, N.Y., and colleagues devised DEEProtect, a system that blunts apps’ abilities to draw conclusions about certain user activity from sensor data. People could use DEEProtect, described in a paper posted online at arXiv.org in February 2017, to specify preferences about what apps should be allowed to do with sensor data. For example, someone may want an app to transcribe speech but not identify the speaker.

DEEProtect intercepts whatever raw sensor data an app tries to access and strips that data down to only the features needed to make user-approved inferences. For speech-to-text translation, the phone typically needs sound frequencies and the probabilities of particular words following each other in a sentence.

But sound frequencies could also help a spying app deduce a speaker’s identity. So DEEProtect distorts the dataset before releasing it to the app, leaving information on word orders alone, since that has little or no bearing on speaker identity. Users can control how much DEEProtect changes the data; more distortion begets more privacy but also degrades app functions.

In another approach, Giuseppe Petracca, a computer scientist and engineer at Penn State, and colleagues are trying to protect users from accidentally granting sensor access to deceitful apps, with a security system called AWare.

Apps have to get user permission upon first installation or first use to access certain sensors like the mic and camera. But people can be cavalier about granting those blanket authorizations, Uluagac says. “People blindly give permission to say, ‘Hey, you can use the camera, you can use the microphone.’ But they don’t really know how the apps are using these sensors.”

Instead of asking permission when a new app is installed, AWare would request user permission for an app to access a certain sensor the first time a user provided a certain input, like pressing a camera button. On top of that, the AWare system memorizes the state of the phone when the user grants that initial permission — the exact appearance of the screen, sensors requested and other information. That way, AWare can tell users if the app later attempts to trick them into granting unintended permissions.

For instance, Petracca and colleagues imagine a crafty data-stealing app that asks for camera access when the user first pushes a camera button, but then also tries to access the mic when the user later pushes that same button. The AWare system, also presented at the 2017 USENIX Security Symposium, would realize the mic access wasn’t part of the initial deal, and would ask the user again if he or she would like to grant this additional permission.

Petracca and colleagues found that people using Nexus smartphones equipped with AWare avoided unwanted authorizations about 93 percent of the time, compared with 9 percent among people using smartphones with typical first-use or install-time permission policies.

The price of privacy

The Android security team at Google is also trying to mitigate the privacy risks posed by app sensor data collection. Android security engineer Rene Mayrhofer and colleagues are keeping tabs on the latest security studies coming out of academia, Mayrhofer says.

But just because someone has built and successfully tested a prototype of a new smartphone security system doesn’t mean it will show up in future operating system updates. Android hasn’t incorporated proposed sensor safeguards because the security team is still looking for a protocol that strikes the right balance between restricting access for nefarious apps and not stunting the functions of trustworthy programs, Mayrhofer explains.

“The whole [app] ecosystem is so big, and there are so many different apps out there that have a totally legitimate purpose,” he adds. Any kind of new security system that curbs apps’ sensor access presents “a real risk of breaking” legitimate apps.

Tech companies may also be reluctant to adopt additional security measures because these extra protections can come at the cost of user friendliness, like AWare’s additional permissions pop-ups. There’s an inherent trade-off between security and convenience, UCLA’s Srivastava says. “You’re never going to have this magical sensor shield [that] gives you this perfect balance of privacy and utility.”

But as sensors get more pervasive and powerful, and algorithms for analyzing the data become more astute, even smartphone vendors may eventually concede that the current sensor protections aren’t cutting it. “It’s like cat and mouse,” Al-Haiqi says. “Attacks will improve, solutions will improve. Attacks will improve, solutions will improve.”

The game will continue, Chakraborty agrees. “I don’t think we’ll get to a place where we can declare a winner and go home.”